Editorial Note

The equal protection framework under the Constitution has taken its most robust form in the manner of affirmative action specifically for socially and economically backward classes under Article 15(4) and backward classes under Article 16(4). The 103rd Amendment Act of 2019 caused a very fundamental break in the status quo by granting reservations to non-OBCs and non-SC/ST persons from economically weaker sections of the population. This has since caused massive debate in both academic, activist and political circles which has only increased since the Supreme Court’s judgment in Janhit Abhiyan v Union of India which upheld the amendment. The questions that arise are many: has there been a removal of the connection between representation and reservation, is economic backwardness an adequate criteria for reservation, what does this mean for existing affirmative action, and what will the implications be for reservations in the future?

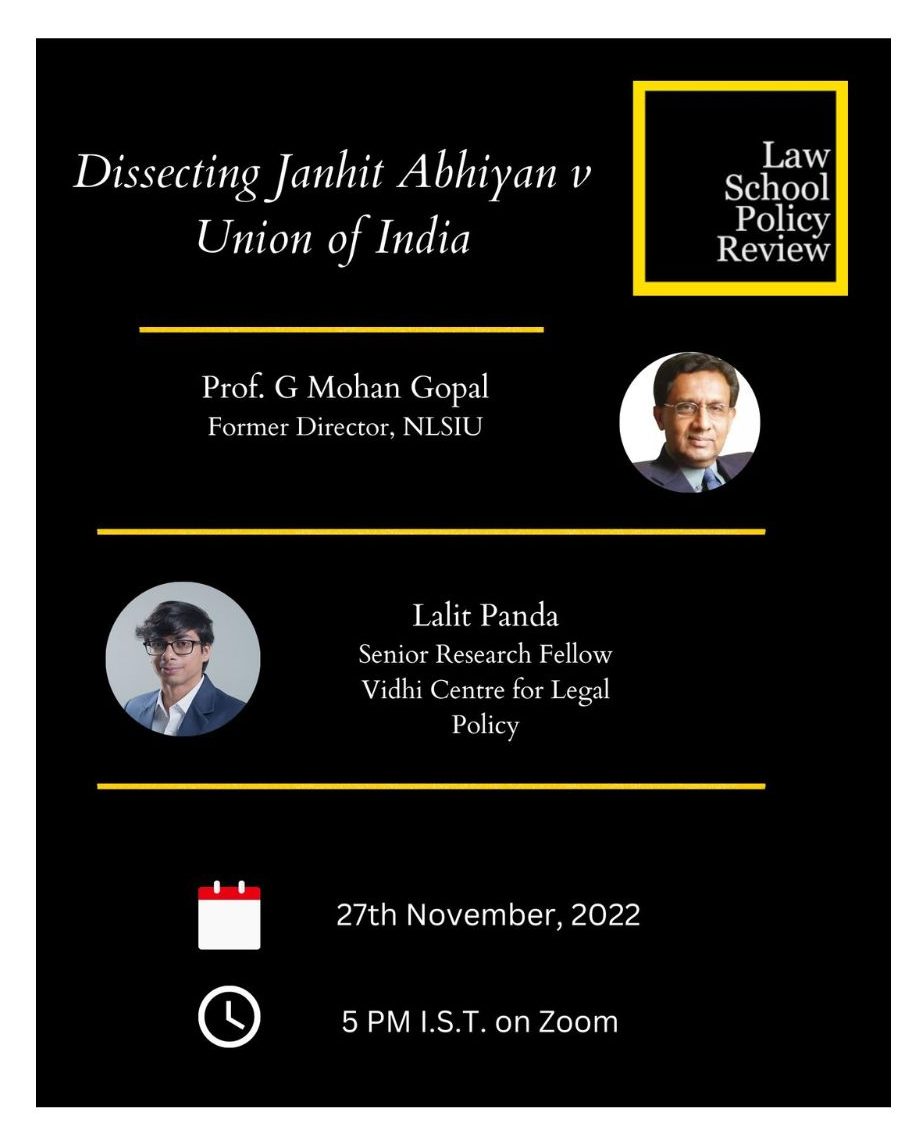

Panelists:

- Prof. G. Mohan Gopal, the former Director (Vice Chancellor) of NLSIU, is actively involved in several constitutional issues and judicial reforms. He also represented the petitioners in this case.

- Lalit Panda, a Senior Resident Fellow at Vidhi Centre of Legal Policy, New Delhi. He studies the Constitution’s equal protection guarantee through a Law and Economics perspective.

The panel discussion was moderated by Niveditha K Prasad, the Deputy Managing Editor of LSPR.

An edited recording of the panel discussion can be found on YouTube.

Opening speeches

The panel started with opening remarks by the panelists.

Mr. Panda began his remarks by framing the questions that the Supreme Court posed in this case. These questions were:

- Can reservations be allowed solely on the basis of economic criteria (and not socio-educational backwardness)?

- Can those who are already availing the reservations (SC/STs) also avail reservation under the economic criteria?

- Can EWS reservations breach the 50% ceiling set by the Indira Sawhney case?

It is the first criteria that is the most interesting as it is a significant departure from the past, where socio-educational backwardness was the criteria of granting reservations. The principal basis on which critics argue against economic criteria being a ground for reservation is that it is qualitatively different. The overall question that he sought to answer was to find the principle that was isolated by the Court and therefore, considered a part of the basic structure of the Constitution. But he agrees that there is use of reservation to serve political or electoral ends. The government and other political parties should be restricted by the basic structure to further unjustified causes which go against the goal of substantive equality.

He stated that there are three ways in which economic reservation is critiqued:

- Reservation deals with lack of representation

- Reservation deals with discrimination

- Efficiency arguments

Firstly, the critics argue that reservation should go to those who lack it and not to those who already are availing it. But this is a misleading argument which assumes a consistent explanation of equality and discrimination. Reservation for one class in the past does not mean that the said class cannot avail reservation on other grounds in the present or the future. An individual can be deprived in more than one aspect and therefore, disadvantage in one ground does not translate into advantage in other grounds. Furthermore, the State has different objectives for promoting reservation. These include preserving the minority character of the State or to ensure formal equality. The doctrine of reasonable classification helps isolate existing State-identified criteria for reservations.

Mr. Panda agreed that poverty can be a ground for discrimination but there do exist other remedies to correct this social ill. Essentially, there should be a morally irrelevant characteristic which can be qualitative or non-valuable, to constitute as a ground for reservation. This is closely tied to the efficiency arguments which questions the efficiency of reservation in alleviating poverty. It is questionable whether distribution of advantages or poverty alleviation schemes cannot work better.

Prof. Gopal began his speech by addressing the key challenge in this entire debate surrounding reservation which is, how do you frame reservation? Here he highlights an irony that it is the backward classes who are anti-reservation as they want only representation. In that sense, the chaturvarna system is also a system of reservation as each caste is designated or reserved a particular job. So, ideally reservation should be for those who are outside this caste system called the “outcastes”. He also argued that those who are anti-reservations love reservations along with the elite, which is why we have different types of reservation in the country like domicile reservation, SC/ST reservation, etc.

Prof. Gopal quoted Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s speech in the First Round Table Conference where he stated the eight safeguards that he wanted for the Depressed classes. Article 16(4) originated from condition No. 5 which is adequate representation in the services. Dr. Ambedkar defined reservation as a “regulation of recruitment” to destroy the monopoly of a few and it is he who was one of the first who proposed that public service recruitment should be subjected to the test of efficiency.

But reservation in its current state is serving the opposite purpose by serving the oligarchy. To substantiate this, he used an analogy wherein the U.S. introduces a similar amendment of reserving 10% seats in government jobs and educational institutes (both public and private) for white people. This would result in the creation of an Apartheid compartment which is precisely what this amendment seeks to do. Through this amendment, it would be the forward classes who would benefit the most. There would be no entry for anyone else.

Another interesting argument made by the Prof. was that EWS is not an economic reservation. As per Article 46 of the Constitution, the primary condition for reservation is to belong to an economically and educationally backward class. It is not only economic backwardness that should be the bedrock of reservations. If that were so, then the Constitution-drafters would have specified or the government should specify.

The professor repeatedly stressed upon the need for representation, instead of reservation. This is because representation brings political power and lack of political power is one of the root causes of poverty. So, his main hypothesis is that representation is the most sacred principle and helps in the sharing of political power.

He concluded his speech by stating that the OBC also has a creamy layer and the forward caste also have a creamy layer which is created by the EWS reservation.

Discussion

Mr. Lalit Panda: The main intent or rationale behind EWS reservation is majoritarian and casteist and is a political project of the State. In order to limit this project, there is a need to find the weak links in it. The facial image of this reservation is based upon a principle which seems to be prime facie defensible. This is similar to other constitutional law subject-matters. For example, even the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019 was projected to be a national security measure but in reality, it is an underinclusive measure to favour one community. This raises questions regarding religiously differentiated governance in India and its impact on substantive equality. The issue involving the Hijab is similar to the controversy surrounding the Sabarimala issue which emphasizes how subterfuge measures are used to serve the majoritarian needs.

There is a narrow possibility of considering EWS reservation as legal. This is when it addresses situations of extreme poverty and when the kinds of goods to be distributed to a certain section of the population is also restricted. This can be countered by the fact that equality is an expansionary measure.

Critics argue that reservation can result in moral hazards as it encourages underperformance. The problem is that there has to be a principled line to distinguish who is eligible for reservation. There is also the issue of over-representation which is premised on the idea that each class or group faces disadvantage in only one aspect and not in multiple. But, this has the potential of alienating the said groups and constitutes as a harm to the purpose of substantive equality.

One way of checking for abuse of reservation is through priority. There are certain groups which have to be prioritized when granting reservation and this has to be checked in its applicability as well. So, anti-discrimination laws should have an in-built mechanism to check for abuse and at the same time, critics should be conscious of the kind of messaging their opinion conveys.

Prof. G. Mohan Gopal: The Union’s Statement of Object and Reasons for initiating this amendment was to provide for educationally and economically weaker sections of the society. The government cannot just pick and choose the criteria that it deems fit for reservation. It is supposed to be both educational and economic criteria, not only economic criteria. The government argues that this stems from Article 46 but this Article in fact, seeks to protect the backward classes from social exploitation and not financial barriers, which is precisely what EWS reservation intends to do.

The point ultimately boils down to representation. There is an oligarchy dominating the three branches of the government and the need is to unseat this oligarchy. It is essentially composed of four communities and we cannot truly consider this to be a democracy. So, deontologically speaking, all groups should be represented as all of them possess different experiences. Within these groups, the most vulnerable should be given preference in this inclusion process, which includes LGBTQ+ individuals. A secular criterion needs to be applied because without it, we would be furthering the upper castes or the socially and educationally forward classes. This creates an elite, apartheid space.

Reservations have a long history in the country and have undergone evolution from 1930 to 1950. The need is to end the reservation of the chaturvarna system and the only issue to be dealt with is at the level of the Constitution and implementation. There is a heavily casteist mindset underlying reservation and this amendment has led to the codification of casteism into the Constitution.

Question and Answer Session

Prof Gopal and Mr Panda graciously answered several thoughtful questions posed to them by the audience.

It is obvious that the EWS reservation is a fraud upon the Constitution, as it favours very few communities who are all wealthy and “upper caste”. However, are there any other suitable reforms that can be imagined?

Prof. Gopal: The prevailing mindset focusses on representation and ignores adequate representation. There is no data to monitor adequate representation but there is a pressing need to regulate recruitment to ensure diversity at even the highest levels of governance. There should be representation of both the forward class as well as the backward class communities to become a truly democratic state. It is only through such representation that we can attack other oligarchies.

Mr. Panda: Representation has different meanings; some consider only its quantitative aspect (i.e., the numbers) while others see its qualitative aspect (level of exploitation). But the commonality here is the identification of backward classes. There is a need for institutional change to identify these classes accurately and to prevent political classification. Further, there is also a need to constitute a secure and independent body like an Equality Commission along with an infusion of priority which gives preference to the worst off amongst the worse.

Do you think that there was a lack of diversity in the bench and on a related note, do you believe the judges had reached a decision even before hearing the petition?

Prof. Gopal: No, I don’t think that the judges had any bias; this was indicated in the transparency expressed by the bench. The dissenting judges were very transparent in their tentative thoughts while hearing the arguments and one could see how their thinking developed. This judgement is one of the most powerful arguments for the need for diversity in the Supreme Court. This can be espoused in this quote by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, “I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life”. Each group has different experiences and all of them deserve the chance to bring these experiences to the table.

Mr. Panda: I agree with the fact that there is a need for diversity which would help the Indian jurisprudence tremendously. All communities and experiences deserve to be represented in the Supreme Court as this would help further the goals of different bodies of law. But I am sort of confused as to whether lack of representation leads to deprivation or is it the opposite?

Prof. Gopal: It is a vicious circle involving representation and deprivation which is often confusing. The idea is that representation of all communities would help in addressing deprivation. The kind of deprivation also varies. It can be individual or group. For the lower castes, addressing group deprivation is important as it helps reinforce their identity and strengthens their solidarity and confidence. Group identities have a monumental impact in the lives of individuals as has been said by Hannah Arendt, “If one is attacked as a Jew, one must defend oneself as a Jew, not as a German, not as a world-citizen, not as an upholder of the Rights of Man”. Atomizing deprivation works on both the individual and group levels. In the end, it is not about efficiency but about fighting an oligarchic society.

This Rapporteur Report was prepared by Aakriti Rikhi, a first-year BA LLB (Hons.) student at NLSIU and an observer with LSPR-KS.

Niveditha K Prasad and Kartik Kalra (editors at LSPR) helped conceptualize the event.